I Heart Formula Feeding (and I don’t care who knows it)

Listen to me read this post here:

Or read the post below here:

Something that I should say first

(I shouldn’t have to, but I know how quickly the mind jumps to conclusions…)

I think breastfeeding is awesome.

My love of formula feeding in no way diminishes your breastfeeding experience.

Infant feeding isn’t a zero-sum issue.

(And by the way, when did it become one?)

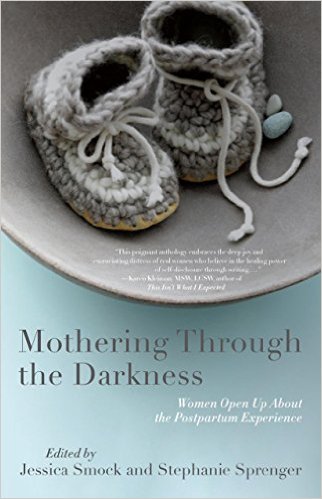

Formula feeding, one week old

As I’ve written about extensively in my book and in other blog posts, breastfeeding was so much worse than childbirth for me. (And I gave birth without drugs).

With my first baby, I was overcome with feelings of guilt (This shit might actually keep her brain from developing as much as it would if I were breastfeeding…) and shame (If I were a better mother, I would have kept pumping, even just a little bit. Every little bit helps.)

In my mind, I wasn’t allowed to openly love formula feeding. Proclaiming how much I loved formula feeding would have been akin to saying that I didn’t particularly care about the health of my child.

That’s what I thought.

When I try to trace back where those thoughts came from, I realize how much of my own insinuations were responsible for the guilt and shame that I felt. I read four or five credible books about breastfeeding when I was pregnant. (The Breastfeeding Book by Martha and William Sears was particularly good.) My takeaway from this and the other books was that, as long as I stuck with breastfeeding, my chances of success were very, very high.

I just needed to buckle down and commit to the process.

Because, let’s face it, breastfeeding is better for me and the baby.

I LOVED THIS MESSAGE.

Because if there’s one thing my friends and family know about me, it’s that I CAN BUCKLE DOWN AND COMMIT like no other.

I’m like a dog with a bone when I move something to the top of the priority list.

And in those first weeks after my first child was born…

Let’s just say, Ruff, ruff.

***

There’s a difference between loving the way that you feed your child and doing it simply because you hate the alternative.

I had to learn this the hard way with my first child.

Because, I confess, I didn’t love formula feeding her.

I just hated the alternative of breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding made me absolutely miserable. It brought me no joy. It only brought physical and emotional pain. Feelings of inadequacy and resentment. And days and days of being awake for 22 out of 24 hours (and that brings you to the brink of psychosis, let me tell you).

So I quietly switched to formula feeding when my daughter was 12 days old. Every time, someone saw us feeding her tiny bottles of formula, the mental tape of guilt and shame ran its course in my mind.

I bit my lip and hoped no one would say anything.

Most people didn’t.

But some did.

And then I was prepared with my boilerplate speech that grew increasingly awkward as I tried to figure out on-the-fly if this audience really needed to know the shape of my nipples or the amount of milk that I was producing. (Does anyone really need to know that?)

It was agonizing.

***

But this post isn’t supposed to be about how hard breastfeeding was for me.

It’s supposed to be about how awesome formula feeding has been for me.

I’ll admit, I didn’t automatically switch to loving formula feeding after having my second baby simply because I had done it before.

But once I realized the absolute deluge of work that having a second child heaped upon us, I was ALL ABOUT FORMULA FEEDING.

With no grandparents living nearby to constantly stop by and help out, we bear the full load by ourselves. (Read: full-time jobs, daycare drop-off/pick-up, hours of housecleaning every day, lawn mowing (a HUGE yard), shopping, doctor visits, dentist visits, blah, blah, blah…)

So trying to breastfeed when my body wasn’t cooperating?

Nope.

Breastfeeding even if my body were cooperating would have been a challenge.

I think the only way I would be breastfeeding right now is if…

1) I truly loved the experience of breastfeeding

and

2) I could hire outside help to pick up my share of the household chores.

Barring those two crucial factors, breastfeeding would just not happen.

Because now, the day is doubly full of responsibilities.

Now, there are no simply no free moments to wade through the quagmire of the Internet and second guess everything that I’m doing and compare this product and that product and this method and that method.

I no longer run Google searches like “infant formula obesity” or “does formula cause diarrhea?” or “comparison of intelligence breastfed and formula fed” or “mother child bonding only breastfeeding?” And then get sidetracked into a discussion board where self-righteous and insecure young mothers tear each other apart.

So unh-uh. Ain’t nobody got time for that any more.

***

If you’ve gotten this far, perhaps you want some specific reasons that I love formula feeding.

Here are my top reasons, in order of importance to me.

- I know exactly how much my baby has eaten (This always helped put my mind at ease in those early weeks when your baby is trying to regain their birth weight.)

- I know exactly what ingredients my baby has eaten.

- I don’t have to worry about how my diet affects my baby. (After ten months of pregnancy, this is a huge relief, I can tell you.)

- My body starts to feel like it belongs to me again, much sooner.

- I can more easily share night feeding responsibilities.

- I don’t have to pump at night or at work, just to keep my milk supply up.

- Actually, just, I DON’T HAVE TO PUMP. (Those machines are like a form of torture, I swear to God. And of course, they were invented by a dude.)

- I don’t have to scrape the bottom of my soul for the willpower to endure a baby’s incessant need to nurse all day, for several days–just to get my baby through a growth spurt.

- I can get a babysitter and leave the house–without wondering how soon I’ll need to pump or nurse before my boobs explode.

- I will never run out of food for my baby–even if my body isn’t cooperating (a statement of middle-class privilege, I acknowledge. Although… so are a lot of these reasons…)

- If I get sick, I can take time to recover without having a baby attached to me all hours of the day.

- I can exercise without worrying about diminishing my milk supply.

- Actually, I can just live life without worrying about diminishing my milk supply.

- I only spend 2 hours per day feeding my child (20 minutes X 5-6 feedings), rather than 4.5 hours per day (45 minutes X 5-6 feedings–that was about the fastest I could ever nurse).

- I didn’t have to worry about whether my baby would take a bottle at daycare.

- I don’t have to confront the frustrating situation of wondering if some nut job is going to find my breastfeeding “inappropriate.” (IT’S NOT. GET OVER IT.)

- I’m sure I could go on…

***

I write this post specifically for mothers who are formula feeding.

Because I know what it’s like to be sitting in a group of moms and overhear someone refer to infant formula as “garbage.” Or hear another mom say, “Well, if that’s how you want to feed your baby…”

It ain’t fun.

And, if you were raised to be “ladylike” like me, you didn’t stand up for yourself. (Instead, you just pretended that you didn’t hear… and then complained about it later to an accepting audience as a means to let off steam. Being female is a bitch, isn’t it?)

What I want to say to you is this:

There will be sooo many times in motherhood when you can’t please everyone, no matter what you do.

This truth hit home hard just a month ago when another daycare mom who was considering withdrawing her baby (who had started just weeks earlier) called our daycare center a “dirty”, “expensive,” “baby factory.” (Expensive, sure, but dirty? Uh, have you been to other daycare centers???) After I told her that I liked our daycare, she said,

“Huh. I just thought my baby deserved better. But you’re fine with this, right?”

Ick. I couldn’t get out of the conversation fast enough.

Trust me. There will always be someone who will try to make you feel badly about how you’re raising your kids. No matter what you’re doing.

And if you need even more assurance that everything’s going to be okay, here’s Adam explaining why baby formula isn’t poison.

Press on, moms.

There will always be someone who is sure you’re not doing the best that you can. (And for some reason, it’s their responsibility to let you know about it.)

Press on.