Book Review: “Mothering Through the Darkness”

by Sharon Tjaden-Burkes

If you’ve never experienced postpartum depression (PPD), it is tempting to write off books on the subject, thinking that they are not good investments of your time. I admit that I paused when considering whether to buy this book. I don’t call what I experienced after my daughter’s birth postpartum depression because it was not long-lasting and as soon as I started getting more than two hours of sleep per day, I vastly improved.

But don’t write off this book.

Because this book isn’t just for mothers who have experienced or who may experience PPD. It’s for husbands and close friends, parents and siblings, doctors and nurses, pastors and counselors. It’s for all of those people who interact closely with women during the postpartum period.

Stephanie Sprenger and Jill Smock, editors of The HerStories Project: Women Explore the Joy, Pain, and Power of Female Friendship (2013) and My Other Ex: Women’s True Stores of Leaving and Losing Friends (2014), have selected and compiled a stunning collection of essays on the postpartum experience that is desperately needed and should be part of the pregnancy literature canon, if there is such a thing.

Mothering through the Darkness is not merely a collection of facts about what women experience during periods of postpartum depression. This is an articulate and engaging collective narrative of thirty-five essays that take the reader through a kaleidoscope of postpartum experiences, ranging from postpartum depression, anxiety, and mood disorders as well as the lesser known post-adoption depression. Some writers sought help while in their darkest hours; others struggled through without help and lived to regret it. But all of these stories succeed in connecting the reader with the foggy inner world of the postpartum period. It is this book’s ability to take the reader inside the mind of the mother that makes it a great read for those who are close to postpartum women.

In the book’s first essay, “Here Comes the Sun,” poet Maggie Smith says, “…we all come into this world unfinished, still stitching ourselves together” (p. 13). The essays that follow uphold this same spirit of honorable incompleteness. The dignity of process and ongoingness. Each essay ends with an understanding that one is never complete, never perfect, never fully finished.

What readers can find in Mothering Through the Darkness are common threads that stitch essays together to create coherence in a chaotic topic. Through Smock and Sprenger’s arrangement of these essays, readers can identify several major themes that emerge throughout the book.

Identity Shift

Not surprisingly, identity shift takes a central role in many of these essays. The struggle of women to redefine themselves as mothers is an extraordinary and monumental transformation. Such transformation is expressed in Denise Emanuel Clemen’s essay, “My Face in the Darkness,” in which she recalls how the birth of her first child created a new reality where “the world was turning upside down” (p. 159). She confuses a rocking chair for a wheelchair. She sleeps at the foot of her bed to watch the baby. This complete upending of her world leads to her profound loss of self.

“I’d lost my old self somehow. The self that persevered. The self that could hold everything in. The self that could ferret out solutions” (p. 162).

This same loss of self emerges in Jennifer Bullis’ “Recovering My Stranger-Self.” After a difficult pregnancy and postpartum period forced her to resign from her tenure-track position at a prestigious university, Bullis sees herself two and a half years later in a mirror and finally feels that she has returned to herself—yet she acknowledges that this new self is, “Not… (her) previous identity, but… someone (she) recognize(s) as capable… as a mother” (p. 119).

Failure

Perhaps the most robust theme among these essays is a sense of failure. In “The Breast of Me,” Suzanne Barston narrates a string of perceived failures before her baby is even born: difficulty getting pregnant, early delivery because of low amniotic fluid, and no euphoric feelings of love for her son once he was born. Soon after that, postpartum depression sets in. In Barston’s words,

“…all I could give him was breast milk. Not love. Not laughter. Not focused attention. My only job was to feed the baby, and if I failed at that, I’d be rendered completely irrelevant. I couldn’t give up” (p. 145).

Katie Sluiter’s essay, “Sometimes There Aren’t Enough Bags of Chips,” shows just how devastating a sense of failure can be when it is coupled with complete physical and mental exhaustion. In her case, her feelings of inadequacy, “turned into a blinding rage directed mostly at (her) husband and (her) mother” (p. 100), culminating with her throwing a bag of chips at her husband while cursing, “FUCK THIS HOUSE AND YOU AND THIS FAMILY” (p. 102).

Emotional Paradox

Women who experience the postpartum period understand the reality of simultaneously feeling multiple, conflicting emotions. Joy, guilt, and terror. Contentment, worry, and gratitude. Sadness, confusion, and wonder. With each emotion vying for its own space to stretch its wings, women can easily fall into the trap of believing that it is not normal for both positive and negative emotions to exist at the same time within the same mind. Not understanding this can drive mothers to feel like liars, impostors, or drama queens.

This is where the essays of Mothering through the Darkness can normalize—perhaps even recreate a new paradigm for—postpartum experiences. Maggie Smith (“Here Comes the Sun”) and Jen Simon (“It Got Better But It Took a Long Time to Get Good”) both refer to the haunting feeling of needing to be away from their babies while simultaneously needing to touch them. Both writers settle on the analogy of a phantom limb to explain how they felt about being away from their babies. Needing and not needing at the same time. The lightness of freedom and the weight of guilt.

Celeste Noelani McLean’s “Life with No Room” not only acknowledges these paradoxes, it shows how identifying these paradoxes helps her move through quandaries that would strike most outside observers as illogical.

“This is the truth. I loved my daughter from the moment I knew that she was inside me. But I also did not love her when she was born. I was tired, ragged, overtaken when she was born. There was no room in my life for me. Knowing this is the truth, that I was not making any of it up, doesn’t fix it. Doesn’t make me love my daughter anymore. But it does make me hate myself a little less” (p. 33).

In fact, McLean’s courage to acknowledge her own suicidal thoughts actually contributes to her ability to overcome them. In simple, powerful words, she explains how.

“I want to be dead, and I admit to this in a way, and it is so embarrassing to admit this. But also, it is a relief. I have spoken these words and I have not died” (p. 33).

Isolation

Perhaps the most poignant essay that addresses isolation and depression is Randon Billings Noble’s “Leaving the Island.” By comparing her journey through the postpartum period to the story of Robinson Crusoe, Noble demonstrates the loss of perspective and disorientation that new mothers can feel when they experience PPD. Although the representation of depression as an island is not new, Nobel’s description of it adds fresh insight.

“It is a place where logic fails…[and] where the laws of gravity are more powerful than any other force. It is a place almost impossible to revisit or describe once you’ve left” (p. 107).

Alexa Bigwarfe shows how feelings of isolation can further intensify PPD in her essay, “Breathe.” With two children, a new baby with a feeding tube, a husband who works all day, and a regimented pumping schedule to keep up her milk supply, Bigwarfe compares her days to house arrest. What saved her was medication and blogging.

“Through the comfort of strangers, I realized I was not alone and I was not a bad person” (p. 228).

Inability to recognize postpartum depression

This last theme is especially heartbreaking in Dawn S. Davies “Fear of Falling,” in which she describes the rift in her marriage that deepens as her husband’s lack of concern and compassion drives her deeper and deeper into depression. Davies recalls her attempt to exit a plane with her baby just before take-off because of her certainty that the plane would crash. When her husband growls at her to sit down because she is embarrassing him, Davies realizes that she must keep her irrational thoughts inside unless she is ready to accept the shame of sharing them.

It is this same tendency of women to soldier through tough times as a testament to their strength that Dana Schwartz takes issue with in her essay, “Afterbirth.” Schwartz opens with the story of her first birth and the large amount of blood that she lost from it. She says,

“I felt a strange sense of pride recounting the story, as if bleeding signified strength, as if almost dying but not was something to be proud of” (p. 39).

But this strength wanes when her baby develops severe colic that keeps her and her husband awake for months. Moving from powerful to powerless upsets her entire world and drives her to a key realization.

“Endurance is not strength; hardships are not badges to be earned. Blood loss is just blood loss, and too much of it will kill you” (p. 42).

The Final Word

Mothering through the Darkness does not leave its readers with feelings of powerlessness. It is full of hope, but not the Hope as seen on Etsy, carved attractively into a wooden frame and then displayed above the mantle like a greeting card that never got sent.

In her essay, “We Come Looking for Hope,” Alexandra Rosas gives hope a more authentic definition. When a nurse recognizes the symptoms of postpartum depression descending on Rosas, she intervenes. The nurse assures her that she will get better because she has seen other patients get better after they got help. Rosas explains that through her postpartum fog, she had to make a decision—between believing that she could get better or being swallowed by depression. She credits this nurse with saving her life. As a result of this dire situation, Rosas creates a new definition of hope, one that rings desperately true.

“Hope is not a continuum—it’s not measured on a spectrum by degrees. It is a complete giving in to a desperate belief in something when you have nothing else left” (p. 171).

There is such truth in the absoluteness of this statement, the way it throws the reader out into the darkness, arms flailing, hoping and praying that there will be something there to grab on to. It’s this kind of candid truth that resonates most deeply with readers.

Although I haven’t mentioned every essay in this review, nearly every essay in this book caught and carried my full attention. They explored themes like the conflict between expectations and reality, healthy and unhealthy coping strategies, antenatal depression, and the darkest thoughts of self-harm and harming others. Their courage to write and share their stories will not only help you to recognize depression, but also to rethink how you can help a new mother who is experiencing PPD.

The writers of these essays do not look away. They look directly at you. They make you see who they are.

They make you see the face of the postpartum experience.

And for that, I thank them.

Buying Information

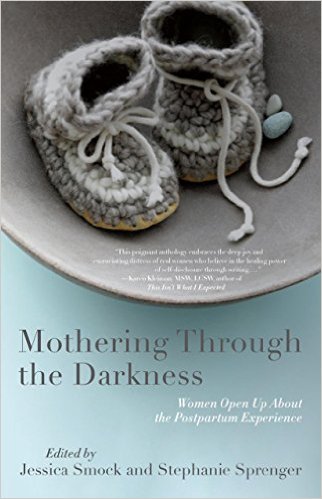

- Mothering Through the Darkness: Women Open Up About the Postpartum Experience.

- Edited by Jessica Smock and Stephanie Sprenger

- She Writes Press: Berkeley, CA. 2015

- Available on Amazon in print and soon on Kindle.

This book looks fantastic! I’m not only going to pick up a copy, but mention it to my therapist as well. Thank you for sharing your thoughts on it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

It *is* fantastic. I could have written so much more, but I also didn’t want to give everything away. I wanted to share just enough for potential readers to see its value. Looks like I did that! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hello. I am trying to compile a list of what makes an outstanding teacher from a parents point of view. I would love you to add your contribution to this google document. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1kLBHg777NEKXfB3kB8OUf3_OrrEPIIF2BundMmsPtIk/edit?usp=sharing

I am trying to collect 100 responses – might be a bit ambitious but I am hopeful. Many Thanks. David

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll take a look when I get a chance. Thanks for passing this on!

LikeLike

I jotted some answers down for you. Take a look when you get a chance! Good luck!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks. These are great. David

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sharon, thank you so much for this thoughtful review. I think this is an important book for all mothers, and not just because I’m in the book 🙂 It’s about the postpartum period, which in addition to possible depression and anxiety, is also about a shifting and rebuilding of identity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for this gorgeous review. You capture the themes that we tried to convey so articulately and beautifully. – Jessica

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure! I truly enjoyed reading all the writers had to say. I hope more mothers and those who support them buy this book. It deserves a lot of readers.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this review. I’m in the book and honored. Just to mention, the last author, her last name is Rosas, not Ross.

Again, thank you for helping to shine a spotlight on this issue.

Jenny

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the correction! I’ll update the post to reflect her correct last name. Your essay was also wonderful. I was especially touched by the conversation between you and your husband about your decision to introduce formula. It reminded me of the conversation that my husband and I had. We’re both blessed to be supported by great guys. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

WOW, what an astounding review. So much work went into this, and I am humbled. We’re lucky when we get someone to thoughtfully put their stamp of approval on the essays here because I’ll bet there is a possibility of people thinking “I don’t want to read a sad book of sad stories.” We need more reviews like this, about how this book is a foot soldier along with us as we walk the rough, unfamiliar and too often in the dark unknown of motherhood. THANK YOU so very much.

LikeLiked by 3 people

You are so very welcome. I’ve always had a heart for writing about the hard stuff and I appreciate it when I see others doing the same–and I’m their biggest cheerleader when they do it well. I truly believe that by sharing these kinds of stories, we build a community of support and neutralize the shame of PPD. And doing that helps more women seek out help when they realize that they need it. I was so very touched by your essay, and thank *you* so much for writing it. This book is on my top list of recommendations now. I hope it sells big time! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This timing of this post is very ironic for me. I just initiated conversations with my Dr last week about probable PPD. It’s so hard to admit that you are falling apart! I’m hoping reading this will help me not feel so guilty or a failure. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 3 people

This book will be a giant hug for you. Trust me on that. Hugs and healing. Be kind to yourself as your body and mind recover. You will get there. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person