God, the Mother

by Sharon Tjaden-Burkes

God, the Father. God, the Son. God, the Holy Spirit.

Adam, Abraham, Moses, Joshua, Gideon, Moses, Samson, Saul, David, Solomon, Elijah, Elisha, Jeremiah, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zachariah, Malachi, Matthew-Mark-Luke-John, John the Baptist, Jesus, Saul/Paul, Peter, James, Philip, Simon, Jude, Andrew, Bartholomew…

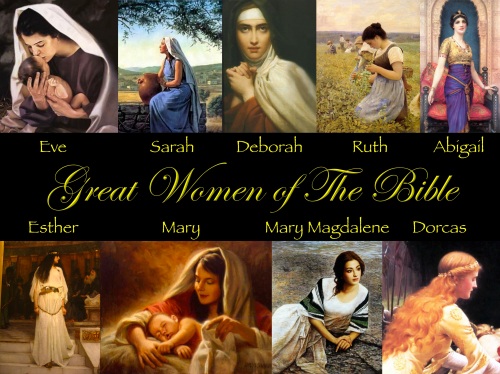

And then there was Eve, Sarah, Esther, Ruth, Naomi, Mary, Mary Magadalene… These are the ones I can remember.

***

How we imagine God makes a difference.

How we imagine God’s followers makes a difference.

***

“For man did not come from the woman, but woman from man. Neither was the man created for the woman, but woman for the man.” 1 Corinthians 11:8

“But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence. For Adam was first formed and the Eve. Adam was not deceived, but the woman being deceived was in the transgression.” 1 Timothy 2: 11-14

***

I grew up in the Southern Baptist Church, where such verses were summoned forth as rationale for explaining the subjugation of women according to the Bible. But I always had a problem with these verses.

Man did not come from woman?

It was clearly a reference to the creation story in Genesis. I understood that. And at the time, I believed in that story. I was taught to read the words of the Bible literally and not get lost in the sticky web of interpretation.

Read the words. Believe the words.

But I could not understand why the apostle Paul was so adamant to throw the creation story in the face of the reader. Man did not come from woman? Give me a break. Men come from women all the time. It’s called birth.

But Eve was deceived, not Adam.

Who cares? I’m not Eve. Hadn’t I been taught that I was responsible for my own actions, not the actions of my ancestors?

I just didn’t get it. Why was it so important to blame women for the fall of all creation?

***

During my senior year of college, I was reading some chapter in a linguistics textbook about the “rhetorical situation”: speaker/writer, message, audience, and context. Then, it struck me.

Women were not the authors of the Bible.

The authors were all men. The people who got to make the decisions about what to put down on paper–they were all men. Men got to decide which women would be mentioned and how they would be represented.

But then, new questions opened up: Why were women left out of Bible stories? Why were their stories less worthy of telling? How had women ended up so powerless in societies throughout the world? Had it always been this way? Were men just naturally stronger and better at organizing political and economic systems?

***

When I wasn’t studying and reading for my other classes, I spent a lot of time in the stacks at the library. Not kidding. I was on a quest to learn more about the origins of Christianity, and I was determined to come away from college with some answers. The more I read, the more I added to my reading list.

And I came across this book:

This book rocked my world.

The author, Merlin Stone, pieces together archaeological evidence and primary texts from a number of ancient civilizations to present a narrative of a grand shift in how people imagined God. In 25,000-15,000 BCE, many civilizations all created similar religions, ones in which the chief divine figure was a Goddess. She was called different names, but in all of these societies, she was revered for her powers of fertility.

Why fertility?

Because we worship what is important to us in our time and in our place.

And fertility was a power so great at that time that it was worth worshipping.

At this time, people didn’t recognize the relationship between sex and reproduction. The idea of paternity was non-existent. Therefore, women were seen as powerful because they had the greatest power of all: the power to give life.

Because paternity was non-existent, children were raised both by their mothers and the community. Mesopotamian societies at this time had mostly matrilineal descent patterns, with children tracing their origins through their mothers. Inheritances were passed from mother to offspring.

In addition, societies that worshipped a Goddess were typically relatively peaceful agrarian communities. Labor was not spent on making weaponry, but rather on growing food, care-taking, and leisure. In short, the Goddess of these communities mirrored what they people valued: the ability to produce and reproduce.

But things shifted.

Stones states that a group of “northern invaders”, also known as the Indo-Europeans, entered into Mesopotamia in wave after wave of invasions for 1,000 to 3,000 years. The timeline is not completely clear since writing systems were not used until about 2400 BCE. This is why we don’t know as much about the Goddess religions. No one was writing it down. The most prevalent and convincing evidence of this time period are the statues of the Goddess found in numerous civilizations.

Indus Valley Terracotta Figurine of a Fertility Goddess, Pakistan/Western India Circa: 3000 BCE to 2500 BCE

Mother goddess Nammu, snake head Goddess figure, feeding her baby – terracotta, about 5000-4000 BCE, Ubaid period before the Sumerians

However, the Indo-European invaders enter the historical record around 2000 BCE, when they established the Hittite civilization in modern day Turkey. Historical accounts of these invaders call these groups of people, “aggressive warriors, accompanied by a priestly caste of high standing, who initially invaded and conquered and then ruled the indigenous population of each land they entered” (p. 64).

Among these warriors were the ancestors of Judaism, which explains a lot of the imagery used in the Old Testament to depict God. (trembling mountains, lighting, fire, etc.) Just as the Goddess mirrored the lives of the people in Mesopotamia, the God of the Indo-Europeans mirrored the lives of the Indo-Europeans. Their God was a young, war-like god. He was a “storm god, high on a mountain, blazing with the light of fire and lighting” (p. 65). Because these people originated from mountainous areas in Europe, they had probably interpreted volcanic activity as supernatural events. Therefore, it’s not such a stretch of the imagination to see how and why the Indo-European God was seen as a god of fire and lightning.

And because the Indo-Europeans were engaged in constant invasions of occupied lands (i.e. what was important to them was conquest), it’s not difficult to understand why the God of Indo-Europeans was a war-like God.

As the Indo-Europeans moved into the area of Mesopotamia, they brought with them their war-like practices, their religion of the storm god, and their patrilineal social organization (if their God was a man, didn’t patrilineal descent seem natural?). As they fought against the societies that worshipped the Goddess, they won. They crushed the previous civilizations with their advanced weaponry.

But it took longer to crush the religion.

***

I won’t go into all of the details of When God was a Woman (it’s far too detailed to do it justice in this single post), but I will summarize Stone’s account of how the Goddess religions were crushed and the new Indo-European God was revered.

As I mentioned before, the idea of paternity in societies that worshipped a Goddess was non-existent. Eventually, people figured out the connection between sex and reproduction. As the Indo-Europeans won more and more land and power, they sought ways to destroy the old religions that stood in their way.

One specific practice of the Goddess-worshipping societies that especially bothered the Indo-Europeans was their sacred sexual customs. In some Goddess religions, temples offered space to people to have sex, which was a form of worship to the Goddess of fertility. Some women lived their whole lives in these temples and were considered holy women. Although the paternity of their children was unknown, their children were not considered illegitimate. They simply took their mother’s name and acquired her status.

This drove the Indo-Europeans nuts. It was completely incompatible with a patrilineal descent system.

After all, how could a patrilineal system be maintained unless the paternity of children could be certain?

And in order to determine paternity…

…you have to control women.

More specifically, you have to control their bodies.

Stone suggests, “it was upon the attempt to establish this certain knowledge of paternity, which would then make patrilineal reckoning possible, that these ancient sexual customs were finally denounced as wicked and depraved and that it was for this reason that the Levite priests devised the concept of sexual ‘morality,’: premarital virginity for women, marital fidelity for women, in other words total control over the knowledge of paternity” (emphasis in the original, p. 161).

So the challenge of the Indo-Europeans was to end the sacred sexual customs. And they did so through demonizing the worship practices of the Goddess religions, which then gave birth to taboos and shame surrounding women and sexuality.

***

It’s not hard to see that the Indo-Europeans were successful. The thought of women freely having sex with whomever they choose elicits words of shame like, whore, slut, prostitute, while men who engage in the same behavior are called studs. Women can’t enjoy sex too much (or risk being labeled nymphos). Women are more judged for having sex before marriage (girls should be virgins at their weddings, but boys are expected “to sow their wild oats”) and outside of marriage (cheating men can be forgiven, but cheating women will be forever shamed.)

***

Hearing this narrative of the predominant religions that once existed and comparing them to the major religions of today helped me understand that there is nothing natural about seeing God as a father. Seeing God as a father makes sense when we see the world through the lens of a patriarchal society. This view of the world is further upheld through religious texts that were written at a time when the Indo-Europeans sought to assert their superiority over the older Goddess religions.

Understanding this helped me to read the Old Testament with different eyes. The authors of the Old Testament were writing from a place of inadequacy. The religion that they were offering people of Goddess-worshipping societies did not appeal to them. Although the Goddess-worshipping civilizations were conquered, their hearts remained true to the religions that had shaped their world for several thousands years.

The writers of the Old Testament were writing for the purpose of redefining their current reality–a reality in which other, more established religions around them conflicted with their long-range goals of asserting widespread domination.

They were writing to redefine “normal” and “natural.”

And they succeeded.

***

As a Christian, I say “God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Spirit” in the liturgy.

But in my mind, I add, “God the Mother, God the Daughter, God the Holy Spirit.”

And when I say “God the Mother” to myself, I feel differently about my relationship with God. When I imagine God as a mother, I feel nurtured, accepted, and loved, regardless of my actions. When I imagine God as a father, I feel fearful and judged, like I must be on my best behavior. That I must put on a good show and not disappoint. (I should add here that my own father was nothing like this. I think my psyche hearkens to archetypal portrayal of fathers in our culture.)

Of course, God is neither man nor woman.

But how we imagine God makes a difference.

***

Other reading if this topic interests you:

- Armstrong, Karen. (2004). A history of God: The 4,000 year quest of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. 2nd ed. Gramercy Books: New York.

- Stone, Merlin. (1976). When God was a woman. Harcourt Brace & Company: Orlando.

Amazing post Sharon.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! That one was simmering for a while.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That makes me feel good. I was wondering if you just whipped it out in minutes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not a magician! Hahahahaha…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Sharon. Haven’t read the book by Merlin Stone but will now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really is great. It’s academic, but she weaves so much information together in a meaningful narrative.

LikeLike

I’m sure I’ll enjoy it – I tend to go for that kind of book anyway.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely love this – thank you!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Glad you liked it! I was working on that one for a while. Finally got it to where I wanted it 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you for stopping by my blog! Keep on writing!

LikeLiked by 2 people

So interesting! I had a hardcore catholic education so many things they told me I took for granted- it wasn’t til I got to college that I started questioning it all (emphasis on the all). This raises so many good points though like the bible being written by men, it always annoys me that Jesus’ own mother never got her own chapter. Great post

LikeLiked by 2 people

An exploration of Mary from a feminist perspective might make an interesting future post… Hmm… 🙂 Thanks for the idea and thanks for stopping by! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] of a male god of creation. If that sounds interesting, please check out my previous post, “God, the Mother.” I’m also combining bits of history and mythology from Turkey and […]

LikeLike